By Sarah Elmquist Squires

Lander Journal

Via Wyoming News Exchange

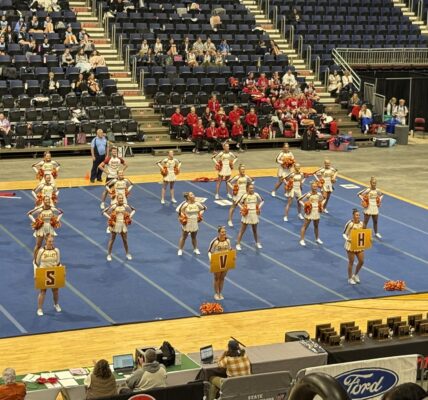

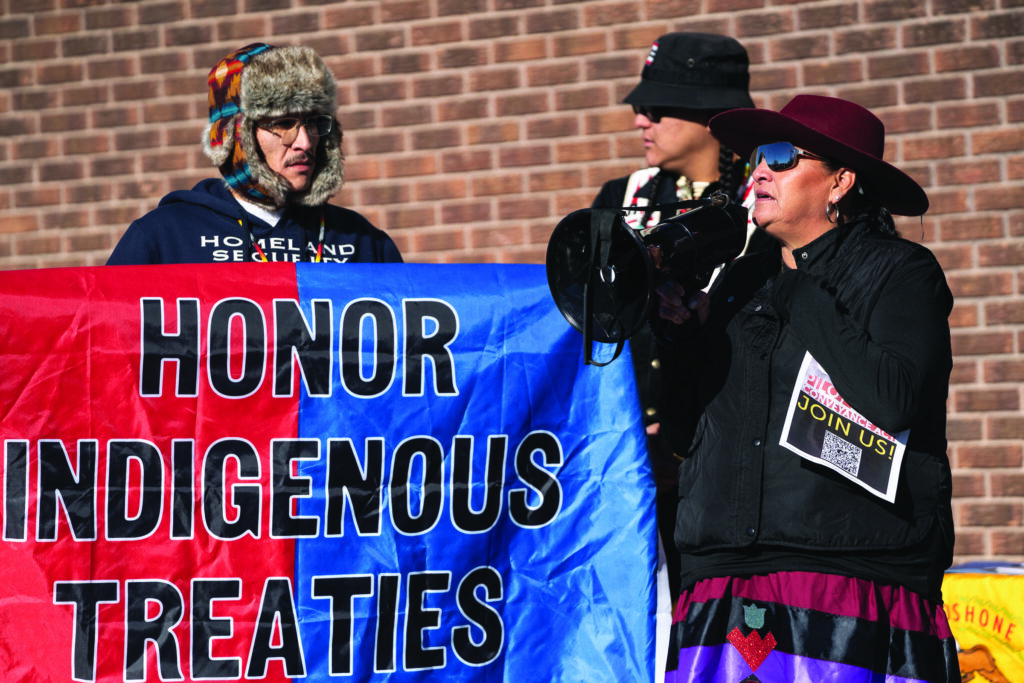

LANDER — Last month, dozens of people stood outside U.S. Senator John Barrasso’s Riverton office, chanting and raising signs in protest.

“Stop Pilot Butte – save our land,” they cried.

The protest aimed to halt movement in Congress on a bill that would transfer ownership of the defunct Pilot Butte hydroelectric plant from the Bureau of Reclamation to the Midvale Irrigation District.

And late last month, they got their wish, after senators from Minnesota and New Mexico blocked a motion to pass it.

The Pilot Butte Power Plant Conveyance Act was first introduced by Rep. Harriet Hageman in the House last year, and was approved there in February 2023.

Barrasso’s move to do the same in the Senate faced much more opposition from tribal leaders who said the tribes were not consulted about the transfer, and that it flew in the face of treaty obligations to return land back to the tribes.

Barrasso’s office insisted it had been in contact with members of both the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes, and that the bill would allow the irrigation district to get the power plant back up and running, rather than costing millions to tear it down.

“The Pilot Butte Power Plant sits on about two acres of BOR land. After 15 years of not being in service, this federally owned power plant was set to be demolished by the BOR,” explained Barrasso’s Communications Director Laura M. Mengelkamp. “Instead of wasting taxpayer dollars to tear it down, the Midvale Irrigation District offered to take ownership of the power plant and make much-needed repairs to bring it back into operation. Senator Barrasso believes this legislation will benefit both American taxpayers and people in Fremont County who would have access to a new source of power.”

After Minnesota Sen. Tina Smith voiced opposition to the bill and said Sen. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico also objected, Barrasso bit back.

“Let me assure the senators from Minnesota and New Mexico that I will be vigilant and watching out for bills that impact at least two-and-a-half acres in their home states,” he warned. “I consider their bills now dead until the Pilot Butte issue is resolved.”

Treaty talks

The old power plant is not owned by the tribes; it’s located north of Riverton on federal land. But opponents to the bill say treaty promises in the past pledged that “undisturbed” land should be returned to the tribes.

The Wind River Inter-Tribal Council passed a resolution in opposition to the bill on December 4 that outlined the history of tribal land reclamation.

Eastern Shoshone Business Council Chairman Wayland Large shared the resolution during last month’s protest.

The 1863 and 1868 treaties outlined the U.S. government’s obligations to the tribes, but in 1905, Congress opened a portion of the Wind River Reservation up to non-Native settlers – leading to Riverton and other towns seceding from the reservation.

Large explained that in1935, an act was passed that reversed this.

With the exception of the land within the Riverton reclamation project, “undisturbed” land was to be returned to the tribes, he said.

For the last 90 years, the tribes have been waiting for the return of some of that land, he explained, and the land that the Pilot Butte Power Plant sits on has been recognized as surplus land to return to the tribes.

“The Midvale Irrigation District has attempted to bypass the tribes’ legal rights,” the Inter-Tribal Council resolution states. “The federal government owes us both trust and treaty obligations to the tribes … The Wind River Inter-Tribal Council is unanimously opposed to this legislation.”

“This is downright theft from the federal government,” Northern Arapaho Business Council member Keenan Groesbeck said during the protest. “Federal government reach – it’s been going on way too long, and it’s time for the tribes to stand up, assert our sovereignty.”