By Sheila McGuire

Uinta County Herald

Via- Wyoming News Exchange

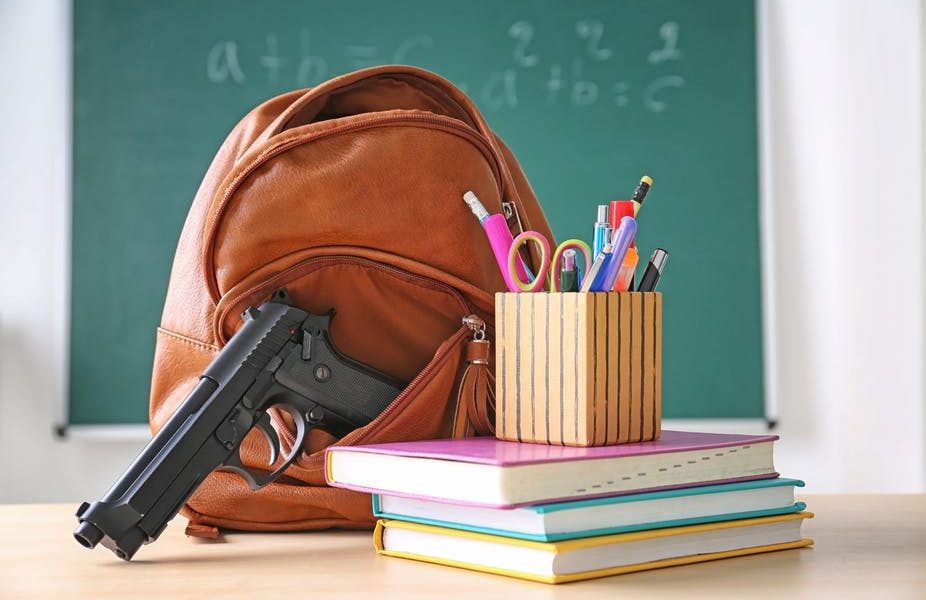

EVANSTON — A hearing was held in Third District Court on Tuesday, Oct. 22, regarding the lawsuit against Uinta County School District No. 1 over Rule CKA, which allows for approved staff to carry concealed firearms on district property.

The suit was filed on Aug. 26, the first day of school, by plaintiffs Tim and Katie Beppler, Nathan Prete and Tiffany Eskelson-Maestas.

Steven K. Sharpe, of First District Court in Laramie, presided over the hearing.

The plaintiffs in the case challenged Rule CKA on the grounds of four complaints, including: • The rule is unconstitutional because of violations of the equal protection clause of the Wyoming Constitution; • The rule doesn’t meet the requirements of the enabling statute; • The Wyoming Administrative Procedures Act (WAPA) requirements weren’t met because the rule is arbitrary and capricious, and • The school district failed to follow WAPA procedural requirements.

Geoff Phillips, attorney for UCSD No. 1, was asked to present first on the district’s motion to dismiss the case.

Phillips argued the case should be dismissed due to lack of subject matter jurisdiction, claiming both that district court is not the appropriate venue to consider a challenge to the constitutionality of the enabling statute passed by the Wyoming Legislature in 2017 and that any petition for review of the rule, which was formally adopted in April of this year, must be filed within 30 days of final action on the rule.

Sharpe had questions about the filing requirements, including whether the plaintiffs could be considered the parties that were notified when the rule was filed with the Uinta County Clerk in April and whether that filing could be considered the date of service.

Phillips argued that, when it comes to rulemaking, the parties are the entire public and the date of service is when the rule is filed.

However, Sharon Rose, one of two attorneys representing the plaintiffs, argued the date of service cannot occur until after the agency takes final action on the rule. In this case, argued Rose, the rule requires both parental notification and law enforcement notification that district staff are, in fact, armed.

Rose said the parental notification didn’t occur until a letter was mailed to parents by the district on Aug. 2, and it is unknown if any law enforcement notification has occurred at all. Rose further argued that plaintiffs had to wait until they were “affected in fact” before filing a lawsuit, which didn’t occur until children went back to school on Aug. 26.

As for the constitutionality argument, Sharpe said he was concerned that perhaps the Wyoming Attorney General should be involved because plaintiffs seemed to be challenging the constitutionality of the law itself.

However, Rose and fellow attorney Michael Rollin argued the plaintiffs aren’t claiming the entire enabling statute is unconstitutional and therefore district court does have jurisdiction in the case.

Rollin said the plaintiffs challenged the constitutionality of the rule itself and not the enabling statute, W.S. 21-3-132, because the statute permitted, but did not require, school districts to develop rules regarding concealed carry of firearms.

Therefore, argued Rollin, it was the district and not the Wyoming Legislature that created a constitutional problem.

Further, the district refused to grant accommodations to parents who requested their children not be in classrooms with armed personnel. Rollin said it was that refusal that violated equal protection rights because the enabling statute says nothing whatsoever about accommodations.

Phillips, however, argued that granting accommodations would be impossible because of the confidentiality requirements of the statute. Phillips said that telling parents certain staff members were not armed would inevitably result in knowledge about which staff were armed.

Therefore, the district was not able to grant any accommodations without violating the statute.

As to the procedural requirements of the WAPA, Phillips said the district went above and beyond the requirements because the school board and administration responded to every single public comment to make sure “nobody was ignored” and because they anticipated there would be legal challenges.

Rose and Rollin argued that it wasn’t enough to respond to every comment and said the WAPA requires agencies to ground actions on evidence and not disregard conflicting evidence. Rollin said the U.S. Supreme Court has required a clear, rational connection between facts and the choices made, which Rollin said “was completely absent in this case.”

Specifically, WAPA requires a statement of principal reasons for adoption of a rule. In this case that statement includes that the board “believes” other security measures are insufficient.

Lawyers for the plaintiffs argued that a “belief” is an insufficient rational basis unless it is backed up by evidence and facts contained in the administrative record, which, they argued, is not the case because all evidence in the record actually points to armed personnel making schools less safe.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys further argued that specific components of Rule CKA clearly demonstrate a failure on the part of the district to thoroughly consider its actions, including a lack of specifics regarding firearm training instructor qualifications, a lack of specifics on what is entailed in scenario-based training and requiring the usage of barrier-piercing ammunition.

The ammunition requirements, in particular, were what Rollin described as “baffling” and evidence that the district “entirely failed to consider an important piece,” which he said the Supreme Court has found demonstrates evidence of arbitrary and capricious rule making.

Phillips argued that every part of creating the rule was done through a committee that included law enforcement and said the district had included the minimum requirements of the statute verbatim.

He further said the statute specifically uses the word “ongoing” because the Legislature intended for districts to be able to continue to refine the rules.

“We know we may need to make adjustments,” said Phillips. “That doesn’t make this arbitrary and capricious.”

Phillips further said district officials are frustrated with some of the complaints in the lawsuit because those concerns, particularly those surrounding the ammunition requirements, were never voiced during the public comment period.

In addition, Phillips said concerns should have been raised during the legislative process when the bill was passed in early 2017, but said, with “the world we live in,” legislators were in a difficult position.

“For the state Legislature to have to make that decision is a terrible burden to bear,” said Phillips, before closing by saying Rule CKA “will prevent a mass shooting” and save lives.

Following oral arguments, Sharpe thanked the participants for a well-argued case on both sides and said he would issue a decision quickly. After oral arguments in the initial lawsuit filed in 2018, Judge Nena James issued her decision approximately two weeks following the hearing. At that time, CKA was ruled null and void for failure to adhere to WAPA requirements, forcing the district to start over with the rule making and adoption process.