Nuclear power winning supporters, but restoring the industry could take more than we think

By Zak Sonntag

Casper Star-Tribune

Via- Wyoming News Exchange

CASPER — Nuclear energy appears to be having a moment. The U.S. and 21 other countries at the climate talks in Dubai last month made a supercharged pledge to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050.

The announcement was anticipated by U.S. lawmakers who’ve earmarked billions to spur the industry at home. Even cultural tastemakers are spreading the word, as seen in filmmaker Oliver Stone’s documentary Nuclear Now, which aims to destigmatize the hot-button topic and make the case that nuclear is our greatest hope for averting climate catastrophe.

Despite the groundswell of support, recent examples show the industry still likes to give folk more than they bargain for, and that the road to a safe and economically viable nuclear energy system remains highly uncertain.

For instance, the Georgia Power Company this year stood up a new nuclear generating facility at its Vogtle power plant. The project is seen as both a major win and simultaneously a glaring disappointment: Though it marks the first such reactor project in the U.S. in more than 30 years, it came in years behind schedule with exorbitant cost-overruns, which are now being shouldered by begrudging ratepayers.

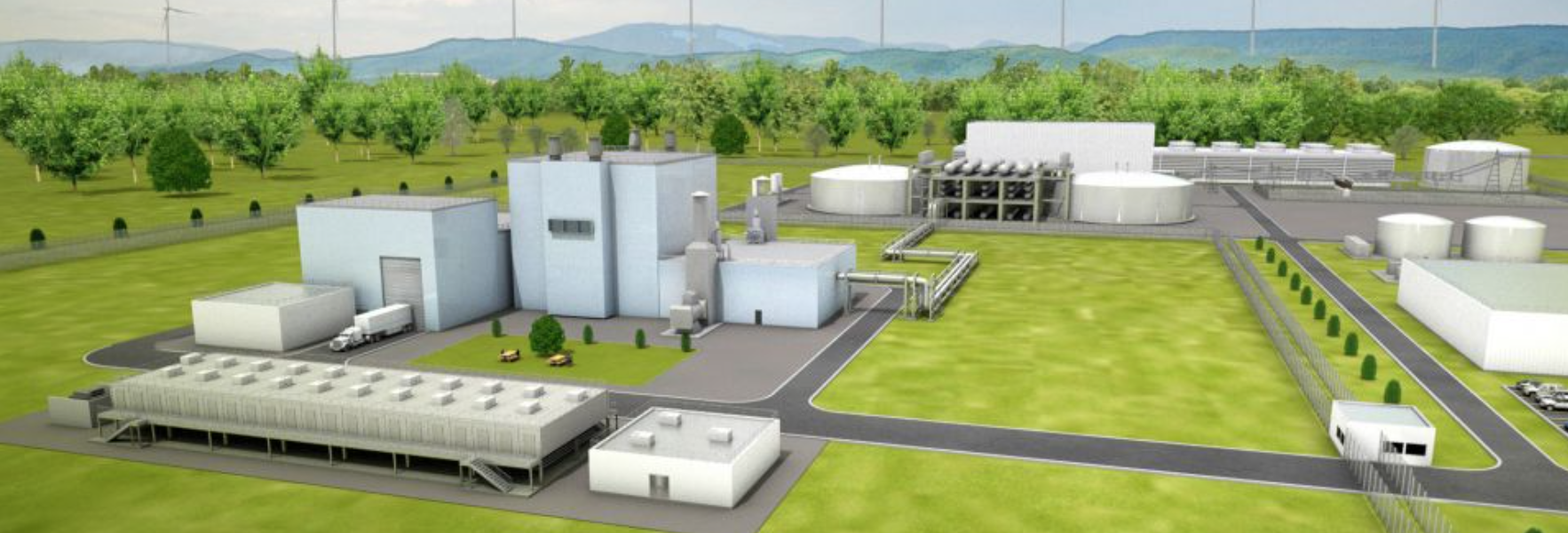

Whereas out west, NuScale, a pioneer in small reactor design, pulled the plug on its decade-in-the-making Carbon Free Power Project, which was slated to provide electricity from its Idaho-based generators to as many as 27 cities around the west. Instead its project costs jumped by almost double to more than $9 billion–all before it could deliver a single commercial watt.

“What concerns me quite a bit is the ability of the industry to deliver nuclear plants, of any type and any size,” Jacopo Buongiorno, director for the Center of Advanced Nuclear Energy Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the Star-Tribune. “In terms of support, I think they are in a good place, but in terms of execution… these projects have to deliver to gain confidence and credibility, not just from the public, but from the investors, regulators, stakeholders and policymakers, etc.”

The setbacks have chipped away at industry morale and have now put more pressure on the Cowboy State to successfully shepherd its nuclear project partnerships. Earlier this year, Wyoming notched a win with the agreement between Tata Chemicals Soda Ash Partners and BWXT Advanced Technologies that sets the stage for the use of small-scale nuclear reactors at trona mines in Green River. Albeit that came on the heels of a major holdup for the state’s most prominent partner, TerraPower, who recently announced delays for its hotly anticipated reactor project in Kemmerer.

However, each of these nuclear projects are unique, and they each shed light on a different challenge facing the industry.

Unlike Vogtle or NuScale, for instance, the delay for TerraPower stems primarily from the nuclear fuel supply chain.

The company initially intended to procure nuclear fuel from Russia, one of the world’s largest exporters of uranium and only commercial provider of the high assay low enriched uranium (HALEU) needed for the new generation of small modular reactor designs, including TerraPower’s Natrium reactor. (HALEU is sold by the TENEX subsidiary of Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom.)

“When Russia invaded Ukraine, it became an option that wasn’t tenable for us. So we’ve had to push our expected service date from 2028 to 2030,” said Jeff Navin, director of external affairs for TerraPower.

The layered supply chain places much beyond the company’s control, Navin says, but if federal programs and earmarks work the way they are intended, nuclear fuel will soon be obtainable domestically.

“Some of it is out of our hands, meaning we need our enrichment partners to take on the same urgency to get this stuff up and running as quickly as possible. And we need the federal government to get this program money out the door.”

The U.S. still procures as much as 12% of its uranium from Russia, which Navin would like to see zeroed out as a way to both level the playing field and incentivize domestic supply.

A uranium ban is amongst other initiatives that have recently won bipartisan support.

President Joe Biden last week signed into law the Nuclear Fuel Security Act, which directs the Department of Energy to establish a program to onshore nuclear fuel production. The law is a big industry win and will fast track nuclear-fuel trade with allied countries, while making money available to expand enrichment capacity and reinvigorate the domestic uranium mining industry.

“It’s time for America to ramp up uranium production so we can eliminate our dependence on Russia. We are stronger and safer as a nation when our nuclear fuel supply chain starts at home,” Sen. John Barrasso, R-WY, one of the bill’s architects, said in a statement.

Uranium mining in the United States has decreased 92% since 1980, according to testimony from John Wagner, Director of the Idaho National Laboratory. And data from the EIA shows that the U.S. in 2021 produced only 5% of the uranium it purchased, most of which is derived from four Wyoming mines.

But mining is only one piece of a much wider supply chain atrophy.

“The supply chain for nuclear power was completely depleted by the fact that we didn’t build any new reactors for more than two decades. So literally, we didn’t have suppliers,” said Buongiorno, who in 2019 led a research project called Future of Nuclear Energy. “Now all of that is being painfully rebuilt, but it takes time, and until we fix those things I’m afraid we’ll continue to see cost overruns and schedule delays.”

On top of federal efforts to bolster the industry, Wyoming’s local leaders are pushing nuclear issues up the priority list. The Wyoming Energy Authority is now inviting bids for nuclear-related projects to tap its $37 million Energy Matching Funds, a program with an impressive record of bringing private capital to the state.

“We produce uranium, but then we send it all over the place to be milled and converted and enriched — all that before it’s actually used in a reactor. Something we’re focusing on heavily in the next year is how to get that fuel cycle here in Wyoming from cradle to grave,” said Rob Creager, executive director of the WEA. “Obviously power is a big thing, but we’re really focused on the whole value chain of nuclear power and what that could mean to the state given our uranium reserves and our expertise in mining.”

In the meantime, TerraPower and others are looking for bridge solutions.

One idea is to repurpose nuclear material from decommissioned warheads, whose highly enriched fuel at over 90% enriched can be “down blended” into the 19.75% high assay low enriched uranium (HALEU) material needed to fuel the new generation of modular reactors. TerraPower and federal leaders have begun negotiations for the use of warhead material.

“Nuclear is really unique. It might be the only thing in energy that has broad bipartisan support. We have full support of the Biden administration… the Senate Energy Natural Resources Committee… the House Energy Committee,” said Navin, who previously served as chief of staff for the DOE. “There’s a lot of things that they don’t agree on, but this is one that they are totally aligned on. Democrats and Republicans across the board have been supportive. Honestly, everything that the nuclear industry has asked for in the past 10 years, we’ve essentially gotten.”

Yet there’s one thing the industry has not gotten. Most legislative efforts are focused on the front-end of production, but with nuclear there’s a significant backend too: radioactive waste.

The current framework for managing spent nuclear fuel comes from a 40-year-old Nuclear Waste Policy Act. The law requires reactor operators to store waste on site in the short term and contract with the federal government to dispose of waste material permanently. However, the storage provision has been woefully unrealized.

“The federal government is now 25 years overdue in meeting that statutory obligation to begin removing fuel from sites,” Joseph Dominguez, President & CEO Constellation Energy, then nation’s largest nuclear power plant operator, testified to congress. Constellation stores its spent fuel in 30-inch-thick concrete casks underground.

And while such methods are considered safe in the short term, experts agree that in the long term the waste must be permanently stored in deep geologic formations. The trouble is no one is eager to host spent fuel.

“There have been blue ribbon commissions, there have been studies, there have been debates, but when it comes down to it, there isn’t a state in the country that wants to be the place for nuclear waste disposal,” said Shannon Anderson, attorney for the Powder River Resource Basin Council, a Wyoming-based advocacy group that is urging policymakers to find a permanent storage solution before moving forward.

In 1987, the federal government legislated a permanent repository site at Yucca Mountain in Nevada. But fierce local pushback has prevented the site from being used.

The Department of Energy now emphasizes “consent based siting,” and has begun offering grants for local communities to explore the viability of hosting spent fuel. The importance of smart storage is underscored by a 2019 federal report tying cancer to nuclear-waste exposure in St. Louis Missouri.

In addition to the plight of these communities, “Inaction by the congress [to find a permanent solution] is fiscally irresponsible. More than $8.6 billion has been paid in settlements and final judgements because congress has not provided a solution. That’s about $2 million a day…due to our inability to establish a program to permanently handle our nuclear waste,” said Sen. Joe Manchin, D-WV, Chairman of Senate Natural Resources Committee, during a committee hearing earlier this year.

Buongiorno hopes the sector as a whole will meet the moment with heightened levels of credibility.

“I’ve been in this business or in this for 25 years and it’s probably the best context I’ve seen in my career in terms of support, support from governments, private investment, media, the stars seem to be aligning,” he said. “But what frustrates me is the lack of accuracy in the initial estimates. People understand that first-of-a-kind projects are expensive and take a long time. But if you promise them it will take this amount of time and it takes three times as long, that’s what will destroy credibility.”