By Angus M. Thuermer Jr., WyoFile.com

Fearful that Chronic Wasting Disease will ravage some 20,000 elk on 23 winter feedgrounds, Wyoming Game and Fish Department launched a statewide initiative Tuesday aimed at untangling a knotted management question: How to avoid disease transmission without starving the population or hurting stakeholders.

The disease that’s spread across three-quarters of the state is likely to shrink populations and turn feedgrounds into CWD hot spots if it infects elk there, a wildlife health official said. Hank Edwards, Game and Fish Wildlife Health Laboratory supervisor, made his comments at the first of four three-hour outreach webinars the agency scheduled for this week.

Game and Fish’s initiative is the first step toward addressing the CWD-feedground dilemma in a process that could take two years or more, said Scott Edberg, the agency’s deputy chief of wildlife. He was clear on one point: “We have no plans at this time of closing any feedgrounds in the near future,” he said.

Game and Fish set a Jan. 8, 2021 deadline for comment on the first phase of what it calls “a challenge we can take on.” There is no vaccine for always-fatal CWD.

Although CWD — a cousin of Mad Cow Disease in cattle and Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease in people — hasn’t been found among elk west of the Continental Divide where the feedgrounds lie, experts believe infection among fed elk is inevitable. There is no vaccine for fatal CWD. Grand Teton National Park biologists discovered CWD in a road-killed deer in late 2018, a stone’s throw from the federal National Elk Refuge near Jackson.

Wildlife managers don’t know how quickly CWD prevalence will increase, what level of infection will affect population levels or whether predators could help limit disease spread. There’s also a question as to how hunters will react if herds are infected at a significant level.

Widespread infection, possibly boosted by artificially concentrated populations at feedgrounds and on the Elk Refuge, could impact everything from tourism to hunting and recreation. But abolishing feedgrounds would have its own repercussions, affecting elk welfare, their numbers, hunters, tourists and even ranchers who might see disease-carrying elk mingle with their cattle herds on winter feed lines. Already the disease has divided the public into pro- and anti-feedground camps.

One thing is certain about the strange nervous-system malady that’s caused by a malformed protein, spread by secretions and may last in the environment for 16 years or more. “Once it’s here,” Edwards said, “it’s going to be impossible to eradicate.”

After the 2019 hunting season, Game and Fish estimated a statewide elk population of 112,900. Among the 28 herds with population estimates, counts came in 32%, or 25,575, elk above the statewide objective.

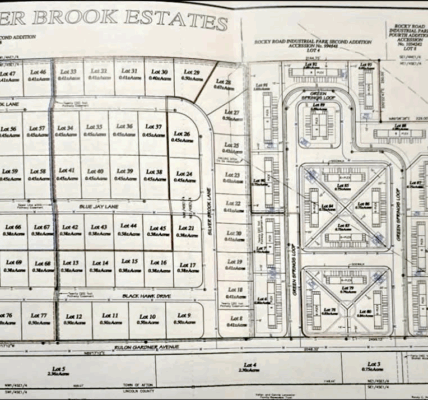

The 14,000 or so elk on state feedgrounds, all west of the Continental Divide, account for about 80% of elk in the surrounding areas, John Lund, regional Wildlife supervisor in Pinedale said. On the National Elk Refuge an average of 7,426 elk annually, or 64% of the Jackson Herd, receive supplemental feed at that U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service operation.

Numbers vary each year, but Game and Fish says approximately 20,000 elk are fed each year in Teton, Lincoln and Sublette counties. Because the issue is localized, Game and Fish separated the elk feedground problem from the rest of its CWD management plan.

Because of the elk abundance, hunters are experiencing “the decade of the elk” Doug Brimeyer, wildlife management coordinator with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, told WyoFile earlier this year. Game and Fish predicted 61,048 hunters would go into the field this season and shoot 25,469 elk.

CWD could change that dramatically and cause widespread social consequences in a state where hunting is a constitutional right and part of the cultural fabric.

The state and private outfitters “want to continue to keep higher populations,” said James Wilder, the wildlife biologist for the Bridger-Teton National Forest. Eight of the feedgrounds are on National Forest property.

Because of the healthy numbers, “we have it pretty good now, sportsman-wise,” Lund told the webinar. “Any significant reduction in elk numbers would be unpopular. That expectation of a robust elk population is real.”

Models show that CWD will begin to decrease elk populations when prevalence reaches 13%, Edwards said. There is no vaccine and no treatment for the malady and an elk can be infected for more than a year before showing clinical signs of the disease.

Feedgrounds could be a source to sustain CWD at elevated levels, he said. Even though there’s scant evidence the disease could spread to humans and cause Creutzfeldt-Jacob Disease or a similar disease, the Centers for Disease control warns against consuming meat from an infected animal.

Even if hunters decide to pursue elk during a period of broad infection, they may find diminished chances as managers impose restrictions to keep population levels up. “Current cow elk harvest in the Jackson Elk Herd could not be sustained at any level of CWD,” said Frank Durbain who manages the National Elk Refuge.

Artificial or supplemental feeding of elk, which started in 1909 in Jackson Hole after many elk starved the year before, seeks to maintain numbers in the face of habitat loss and disruption of historic migrations. In 1929 Game and Fish began feeding in the upper Green River drainage, high up along the Gros Ventre River and at the confluence of the Snake, Salt and Greys rivers near Alpine, Lund said.

A key element of the program was the Wyoming Legislature’s decision to set up a big game damage-claim system under which stockmen and -women would be compensated for cattle feed consumed by elk.

“It was easier,” and less expensive, Lund said, “to move elk to feedgrounds.”

Cost of feed isn’t the only issue for Game and Fish. Elk can carry and transmit the bovine disease brucellosis, which causes miscarriages in both species. Feedgrounds help separate elk from ranchers’ herds, especially when elk are most contagious.

Feedgrounds also keep elk off highways and free native winter range for other species such as deer.

The state feeding program cost $1.6 million last year. It requires the purchase of between 6,000 and 9,000 tons of hay annually, plus difficult transport to remote feedgrounds.

Game and Fish contracts with a small but hearty band of elk feeders, many of whom drive horse-drawn sleighs, to dole out hay bales each year. Elk get between eight and 10 pounds of hay every day and are fed an average of 123 days a winter. Feeding reduces the average mortality on feedgrounds to 0.8%.

Hunters buy a $15 special management permit to hunt in the areas where elk herds are fed, but that covers only about 10% of the feeding costs. It would take “a pretty good increase” in permit prices, Lund said, to cover the feeding program.

“Trying to make hunting affordable is something we need to keep in mind,” he said.

Natural predation could be a tool to weed out infected animals, Edwards said. Researchers know mountain lions selectively prey on CWD-infected animals, he said. Some researchers of wolf predation believe wolves may be able to identify those animals that are CWD positive “before they’re showing clinical signs,” he told the group.

In recent years Game and Fish has sought to reduce elk dependence on crowded feedgrounds following several attempts to fight bothersome brucellosis. The disease can cause human sickness too, most commonly through the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products.

Despite bovine vaccines, brucellosis has infected more than 20 cattle herds in Wyoming since 2000. Though hunters freely consume feedground elk because any Brucella bacteria die during cooking, the USDA frowns on consuming infected cattle.

Federal regulations have led to the depopulation of some Wyoming ranchers’ stock. Although brucellosis and CWD are very different diseases, “you cannot disentangle the two,” said Brandon Scurlock, Game and Fish’s Pinedale wildlife management coordinator.

In the battle against that disease, Game and Fish has been confounded despite decades of effort. Vaccinations were shown not to work among Cervus Canadensis. A test-and slaughter program at the Muddy Feedground south of Pinedale also failed.

As soon as the five-year Muddy program that entailed the killing of test-positive elk ceased, infection rates soared to pre-program levels. Brucellosis also is as prevalent in some free-range herds as it is on feedgrounds, experts said.

Game and Fish also has developed individual plans for feedgrounds that consider neighboring ranches and stock, surrounding winter range and other factors. Generally, those plans seek to start feeding only when necessary and to not unduly prolong it in the spring. In some instances, feeders now spread hay out over larger areas to keep elk farther apart to limit disease spread.

A CWD feedground plan will be developed over the next 18 to 24 months with “lots of opportunities,” for people to submit their ideas, Edberg said.

People can comment and, starting Dec. 10, can see the webinar, at the Game and Fish’s website.