By Katie Klingsporn, WyoFile.com

July 23 was the kind of muggy midsummer’s evening where school is the farthest thing from most people’s minds — a distant obligation that comes after the vacations, barbecues and long days off. But in Lander, as more than 100 people filed into the high school auditorium for a meeting of the Fremont County School District #1 Board of Trustees, it was clear that the school system weighed heavily on the thoughts of this community.

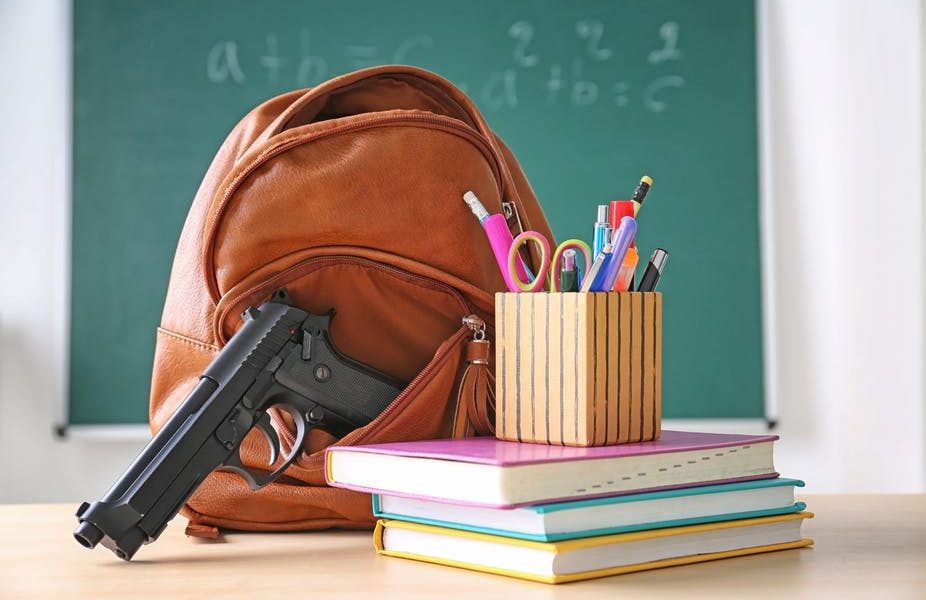

One-by-one, people stepped forward to share their perspective on a proposed policy that would allow qualified, volunteer teachers and other district employees to carry concealed weapons in the district’s schools for the purpose of school safety. Nearly 60 people — parents, teachers, employees, retired law enforcement officers, even students — took turns at the microphone.

About 80% spoke in opposition, expressing a belief that the policy would only make schools more dangerous and imploring the board to at least slow down and take more time to study the matter and deliberate.

Others spoke in favor, saying school staffers can act as a crucial line of defense in the unlikely worst-case scenario of an armed intruder. At times, voices cracked with emotion.

Stances differed widely but all who spoke shared a common goal: the safety and well-being of the community’s school kids.

After two hours of statements — and on the heels of 22 months of consideration that included surveys, comment periods and meetings filled with emotional public testimony — the board, with little fanfare, put the matter to a vote. The measure to allow concealed carry in Lander’s schools passed 4 to 2. By that time, the hour was late, and most of the public had gone home. The vote elicited little reaction.

The following day, Vice Chair Joe Palladino told WyoFile he voted for the policy because it was the right thing to do.

“I didn’t hear any arguments or any discussion that was convincing enough for me to change my mind. I think the schools are safer with some armed staff,” said Palladino, who has worked as a psychologist in local schools for 42 years. He acknowledged that opponents were well organized and passionate, but said he believes he was elected to make informed decisions that are the best for the schools.

“Overall I think I have to vote with my own head and my own heart,” he said. “That’s why it’s a representative board, and that’s why we make the decisions. That’s why I voted the way I did.”

For Rose Steller Burke, a mother of three who had been a vocal opponent of the policy, the meeting represented the end of an emotional rollercoaster that left her deeply disheartened — about public governance, about the heightened risk posed by guns in school, about the safety of her children in what should be a haven.

“As an eternal optimist I was really hopeful going in that the process would be one that I could really believe in,” she said. Instead, she said, the board failed to address the concerns, the opposition, even the suggestions to improve the policy that people posed. There was no discourse with the public, she said. “That was really frustrating to me. It just feels like a lot of steps were skipped and that this was just a policy that they wanted, no matter what. It was really shocking.”

Lander’s story is the latest of a Wyoming community grappling with the question of arming school employees. It’s a question that the Wyoming Legislature made possible in 2017, when it adopted House Bill 194, the School Safety and Security Act. The act empowered individual school boards to determine for themselves whether to allow trained and qualified school employees to conceal carry guns on campus as a matter of safety.

With its adoption last week, Lander’s school district became the fourth in the state to approve a guns-in-schools policy, joining Uinta County School District #1 (Evanston), Park County #6 (Cody) and Washakie County #2 (Ten Sleep).

Most of the state’s 48 districts have not taken up the issue — according to a WyoFile poll of state superintendents, 43 districts have either not acted on a policy, or discussed and opted not to move forward on one. Campbell County #1 (Gillette) is in the information gathering phase but has yet to draft a policy.

The handful of districts that have waded into the relatively uncharted waters have found emotionally charged conversations and reminders of just how polarizing the topic is.

“It really does galvanize the community,” said Niki Tisthammer, a retired teacher in Cody, which in April 2018 became the second school district in the state to adopt a concealed carry policy. When the issue came up in her town — which is internationally famous for its Wild West gun culture — Tisthammer, an opponent, said the public conversation was extremely contentious.

Because while it’s clear both sides of the issue have the same intent — creating the safest possible environment for students — their visions of how to accomplish that are diametrically opposed. To proponents, allowing school employees to carry weapons adds an extra layer of protection; to opponents, it heightens the risk.

Brett Berg, Fremont County #1 board chair, said these approaches could not be more different.

In Lander, he said, “It didn’t surprise me at all that it turned into a polarizing, divisive policy.”

The debate is further complicated by conflicting research, intense nationwide anxiety about school safety and the fact that guns remain one of the nation’s most schismatic topics, even in a weapon-friendly state like Wyoming.

“It’s divisive to these little towns for sure,” said Tim Hudson, a carpenter whose son attends school in Lander. “It’s making people mad. But at the same time, it’s making people get involved. It makes people come to school board meetings, myself included.”

In 1999, the nation was rocked to its core when two teens went on a shooting spree at Columbine High School in Colorado, killing 13 before taking their own lives. In the 20 years since, school shootings have proliferated — more than 230 have taken place, according to the Washington Post, exposing some 130,000 children to gun violence.

With each event, the conversation around school safety, gun control and mental health has heightened, and the norms for school safety have evolved. These days, schools regularly conduct safety audits and armed intruder drills, enforce strict access restrictions and check-in policies, operate sophisticated surveillance systems and employ school resource officers (SROs).

Some states have further addressed the threat by allowing employees such as teachers, counselors or coaches to carry firearms. In Utah, school employees with valid concealed carry permits have been able to carry firearms in schools since 2003, and are not required to notify their administration. In Colorado, at least 30 school districts and charter schools allow teachers to carry guns, despite the fact that there is no statewide training standard. Idaho, Florida and Texas also allow concealed carry.

Wyoming was not the first state to allow guns in schools, but the handful of districts that have taken it up here have still had to figure out the nuts and bolts of how such policies work as they go. Small town school districts and volunteer school boards have had to create frameworks for training and licensure requirements, establish drug testing and psychological evaluation processes and balance complex issues of privacy and transparency — all with few models to glean from.

Michelle Escudero, a Fremont County #1 school board member who cast one of the no votes on the policy, says drafting, evaluating and implementing a policy creates a massive research burden on small districts like hers.

“We’re small enough that this becomes a huge drain of time, money and resources,” she said. And then there’s the Pandora’s box of heated public debate that it springs open. To Escudero, it feels like the Legislature “just passed the buck,” serving up a massively complicated problem for little districts to sort out.

For Uinta County #1 (Evanston), crafting and enacting the state’s first policy was a bumpy ride. Shortly after hastily passing its policy in March of 2018, the school district was sued by a community member for not following proper public procedure. A judge sided with the suit, nullifying the policy and sending the district back to the drawing board. (It passed the policy again in April of this year.)

Sheila McGuire, a reporter who covered the issue for the Uinta County Herald, said the state statute leaves quite a bit of leeway to individual districts.

In Evanston, she said, “everyone has learned a lot about maybe having to slow down. Some clarity probably would have been helpful [from the state] about what kind of procedures they needed to follow.”

Alison Frost and her family moved to Lander in 2011. Frost found a community with exceptional schools, where her children’s experiences in the classroom have been overwhelmingly positive. But when she caught wind in late 2018 that the school district was considering a concealed carry policy, she was aghast.

“I thought, ‘oh my gosh, how could this ever happen here?’” Frost said. To Frost, putting weapons in the hands of the people responsible for teaching students is a not only an inappropriate burden on educators, but one that can lead to horrific accidents. She believes arming employees should be considered as a last measure, not a first.

“I’m not opposed to guns in schools, I’m not opposed to SRO officers or even private security consultants carrying weapons. I’m opposed to guns being carried by civilian volunteers,” she said. “It just feels like putting the cart before the horse, and I feel like it’s going to make our schools less safe.”

Tim Hudson agrees. The lifelong Wyoming resident, who has seen his fair share of gun-related accidents as a former EMT, says he can think of many better ways to go about increasing school safety, such as increasing mental health resources, finding money to put SROs in every school and fortifying buildings.

“Non-lethal means of defense sort of makes sense to me as a good place to start,” he said. Hudson, whose family has lived in the state for generations, added that his stance isn’t about an anti-gun agenda. “I’m a gun owner, and I think most of the opposition to this policy probably are too. This is not about guns, this is about risk management.”

After discovering the board was exploring a policy, Frost began attending every board meeting, researching the issue in depth and soon found herself at the head of a de facto campaign to oppose the measure. She shared resources, shot off emails and put together a fact sheet citing organizations like the National Association of School Resource Officers and the renowned ALICE Institute (which offers active shooter response training), both of which frown on the practice of arming volunteer school employees.

Meanwhile, the school district moved forward with its own investigation.

It surveyed staff. Of the district’s roughly 350 employees, 159 responded, according to Superintendent Dr. Dave Barker. While 47% said they would support allowing staff to carry, 38% said they would not and 15% said maybe. Fourteen percent, meanwhile, responded that they would apply to carry under the policy. The district then created a community survey, which came back with 53% of respondents saying they would support a policy. Frost, Hudson and others have questioned the scientific validity of the community survey, which they said could be taken multiple times.

In February of 2019, the board passed a motion to develop a concealed carry policy for the district. The policy that resulted passed on first reading in May after emotional public testimony — the majority in opposition according to Frost and Hudson — that touched on everything from accidental discharge to psychological effects and so-called soft targets.

Proponent Scott Jensen, an FBI agent and father of seven, told WyoFile the issue for him comes down to the concept of “depth of defense.” The idea is to create many layers of defense so if one fails, any of the various others can be employed.

“Putting an SRO in every school would be good … but that’s not a failsafe in itself, as we saw in Parkland, [Florida],” he said. Jensen noted that Lander’s policy is built so employees who wish to carry must meet very rigorous standards that exceed the statutory guidelines.

“It’s a big commitment and a big responsibility,” he said. “My hope is there will be a handful of teachers and staff members who are willing to take on the extra burden. And then if the worst thing would happen, they’ll be there.”

School board member Jared Kail was also a prominent voice in the fray. He authored an 18-page position paper laying out his reasons for support that, like Frost’s, cited supporting material — including the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission report, which recommended the state of Florida allow qualified school employees to conceal carry.

In his document, Kail too stressed that it’s about creating the most comprehensive network of safety possible. Fremont County #1’s policy, he noted, is just one part of the district’s ongoing framework of safety; it complements other pieces like mental health counseling, facilities safety, ALICE Institute training and SROs.

“This is a pragmatic issue that recognizes the reality of today: it is possible for a weapon to make its way into our school setting regardless of how hard we work to keep them out,” Kail wrote. “A staff member armed with a gun is our last line of defense when the unthinkable happens and our kids’ lives are at stake.”

In the 45-day comment period that followed the board’s first reading of its policy, 286 written comments poured in, according to records compiled by Superintendent Barker. Of those, 217 — 75% — were opposed. The school board met July 23, the day after that comment period closed, took oral comment from nearly 60 community members and passed the measure.

Chairman Berg said the board spent dozens of hours hashing out the policy; it was not something members took lightly.

“We have a lot of people in the community that are opposed to the idea of staff carrying firearms, and I get that. I just disagree with it,” he said, noting that local law enforcement’s support of the policy helped seal his decision.

“It’s unfortunate that this turned out to be a gun thing, rather than a safety thing,” Berg continued. “I wish we weren’t at this place in society where we are having to talk about arming school staff to protect our students. But in reality that’s where we’re at.”

Different iterations of the conversation have played out from Powell to Gillete and Ten Sleep.

In Cody, where the policy is entering its second school year, Superintendent Ray Schulte reported that employees are using it, but could not disclose specifics due to confidentiality. He did note that it isn’t really a point of discussion any longer.

“We managed to gather the information, make the decisions and move forward. Certainly there was emotion involved in it. I think all in all, it was managed well enough,” he said. “It’s gone well so far.”

In Fremont County #26 (Shoshoni), the district and board wrestled with the issue for a year and a half. After much discussion and research, the board opted to forgo a policy and instead search for an SRO.

Campbell County School District in Gillette, meanwhile, is in the middle of the conversation. The district has put out two surveys, met with law enforcement, held three listening sessions packed with community members and is still processing the information. As the state’s largest district geographically,

Superintendent Alex Ayers says there’s a lot to consider, and the board intends to be deliberate.

“It’s been a long, patient process with lots of feedback,” Ayers said.

As the former superintendent of Park County #6 (Meeteetse) and the current superintendent in Park County #1 (Powell), Jay Curtis has been involved in two very different conversations about concealed carry. In Meeteetse, Curtis was a huge proponent for concealed carry. (Though the school board there ultimately opted against adopting a policy).

In the large and very remote district, Curtis said, it could take the sheriff’s office 20-40 minutes to respond. “And if you have someone in the school district intending harm, that is an eternity.” He felt armed employees could fill the gap.

But in Powell, he notes, it’s a different community with different resources and different needs. It’s more populous, with a spacious high school and closer proximity to law enforcement.

“I decided to take the board down a little bit of a different path,” he said. Instead of passing a concealed carry policy, the Powell school board built a comprehensive safety plan that touches on everything from response training to interagency collaboration with law enforcement and social emotional learning. It does leave the door open to consider a concealed carry policy in the future. But Curtis says one thing he has learned is that school safety is not a single-solution problem, and there’s no one-size-fits-all answer.

“I hope this doesn’t come across as judgmental because it’s not. School safety is so much bigger than concealed carry. Anyone who boils it down to, ‘our kids would be safer with [concealed carry policy]’ is simplifying … it’s a very complex problem and requires a very complex approach,” Curtis said.

In Lander, parents like Frost and Hudson are contemplating how to move forward. Both have considered taking their children out of the district, but say their kids love their schools.

Hudson said he wasn’t surprised by the outcome, which felt predetermined to him. But he was disappointed by the process. All he can do now is remain involved in the school board and its 2020 election, he said. Ultimately, he levels his frustration at the Legislature for creating what he sees as more of a problem than a solution.

“It’s just such a shame that it’s so divisive in a community, an otherwise relatively close-knit small town. It’s just tearing people apart,” Hudson said. “I still blame the legislature for the mess we’re in.”