By Ellen Gerst

Casper Star-Tribune

Via- Wyoming News Exchange

CASPER — In 2019, Desirée Tinoco started a Facebook group after hearing about two men missing in Wyoming, whose cases weren’t getting much coverage.

“You see a little kid go missing and the whole town stops and knows about it and wants to hear about it,” Tinoco says. “But if it’s a Native American, or a middle-aged man, or someone out hunting or somebody with a drug history, all of a sudden they’re no longer somebody’s baby.”

If just three or four hundred people joined the group, she thought, it would be a success.

Now, the page has more than 11,000 members. Some days see five new posts looking for missing children and adults, some see zero. Most are found within a couple days, Tinoco says, but the older the person is and the longer they’re missing, the harder it gets to track them down — even with thousands of eyes on the lookout across the state.

With roughly 50 people missing statewide at a given time, Wyoming is consistently ranked in the top 10 states for missing people per capita, and doesn’t have a uniform database to keep track of all the reports.

The next step, Tinoco says, is going to the Wyoming Capitol to change that.

While Facebook is a good platform for spreading information fast, it isn’t a replacement for a state-maintained database. There are spam accounts to deal with, Tinoco says, and posts can easily get buried in the group feed on an active day. And without a uniform reporting system, she says it’s hard at times to confirm basic information about people reported missing on Facebook.

Tinoco, who lives in Casper, has formed alliances with law enforcement, Casper city government and other citizens to gather insight on the state’s current protocol for missing persons and support for a bill she hopes can be introduced in the spring’s upcoming legislative session. Last week, she presented her project to Casper City Council (for the second time in a year) and got unanimous council support in return.

Earlier this summer, she delivered a petition with more than 30,000 signatures to Gov. Mark Gordon, demanding a statewide missing persons database for Wyoming. When she heard back from his office, Tinoco says she was shocked to hear they were eager to get on board with whatever legislation comes out of her efforts.

“The more effort and focus on it, the better off we are,” Tinoco says.

Tinoco says she’s looked to South Dakota’s missing persons clearinghouse, established just last year and managed by the state’s attorney general, as a guide for a possible system in Wyoming — but every other state in the region has one as well.

It took a long time and a lot of unreturned calls and emails to find a lawmaker to write and sponsor the bill in Wyoming, Tinoco says. For a while, she thought she would have to write it herself.

But eventually, Casper administrators connected her with Rep. Art Washut, R-Casper. With nearly six months until the next legislative session gavels in on Feb. 14, the effort to get the missing persons issue on the discussion floor is still in its very early stages.

In the meantime, Washut says he’s recommending the Joint Judiciary Committee study the issue along with other juvenile justice topics on its slate during the interim. Forrest Williams, the director of the Wyoming Division of Criminal Investigation, and DCI Criminal Justice Information System Deputy Director Allison Moore are both scheduled to be at the committee’s next meeting in Cheyenne starting on Sept. 13.

Williams said DCI’s involvement is still in its early stages, but the agency is already working on figuring out how to refine its missing persons protocol.

“We’re going to take a look at our processes and procedures for missing persons and see where we can improve,” Williams says. “We need to have a more robust reporting system.”

Right now, police departments, sheriff’s offices and other law enforcement agencies are all responsible for reporting their missing people to DCI through the National Crime Information Center, and the central agency then enters them into a spreadsheet.

A more streamlined system, Williams says, would aim to collect the same set of information for each missing person, no matter which agency reports them. The division is in the process of looking at systems and databases in place in neighboring states to figure out how best to improve reporting in Wyoming.

“If the right questions are asked on the front end, then if unfortunate circumstances lead to an investigation we make sure that pertinent information is gathered at the onset,” Williams says.

In Casper, the police department has already lent its support to the effort to create a database and increase accountability for law enforcement agencies dealing with missing people. The best way to do that, Capt. Shane Chaney says, is to implement a tighter timeline for reporting the case and all the pertinent information.

There’s already a timeline in place at the Casper Police Department for children who go missing — the officer must input that data as soon as practically possible. Most of those juvenile cases are solved quickly compared to older people.

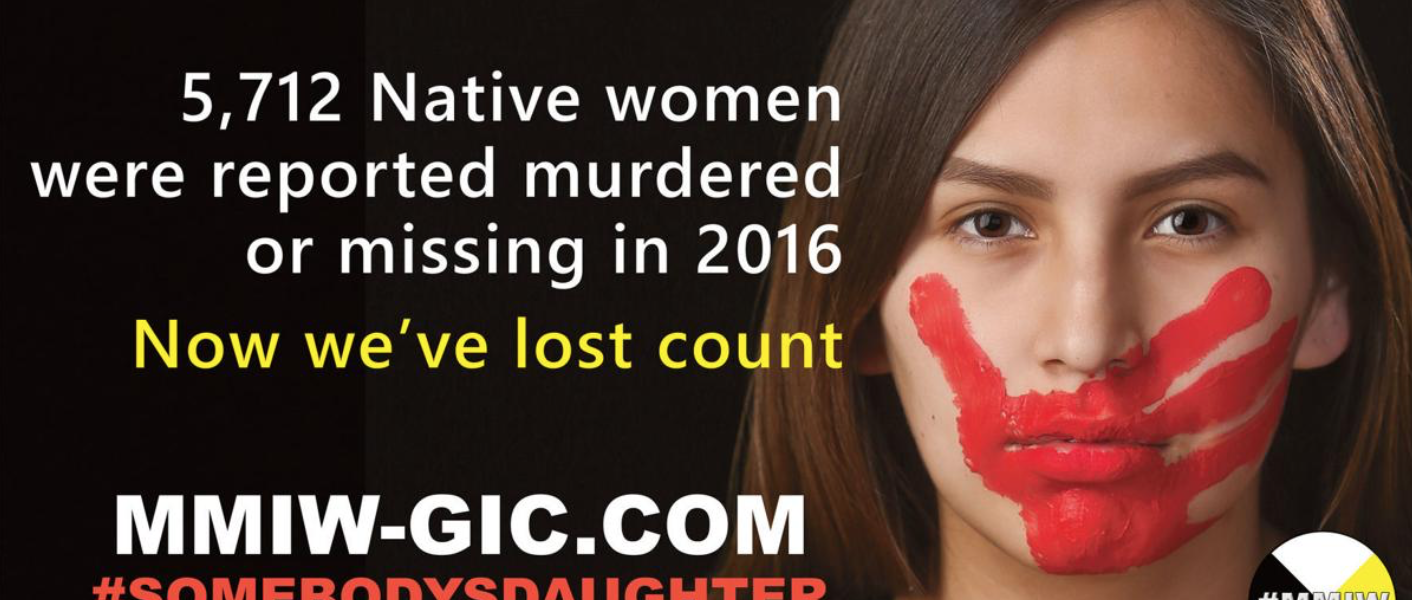

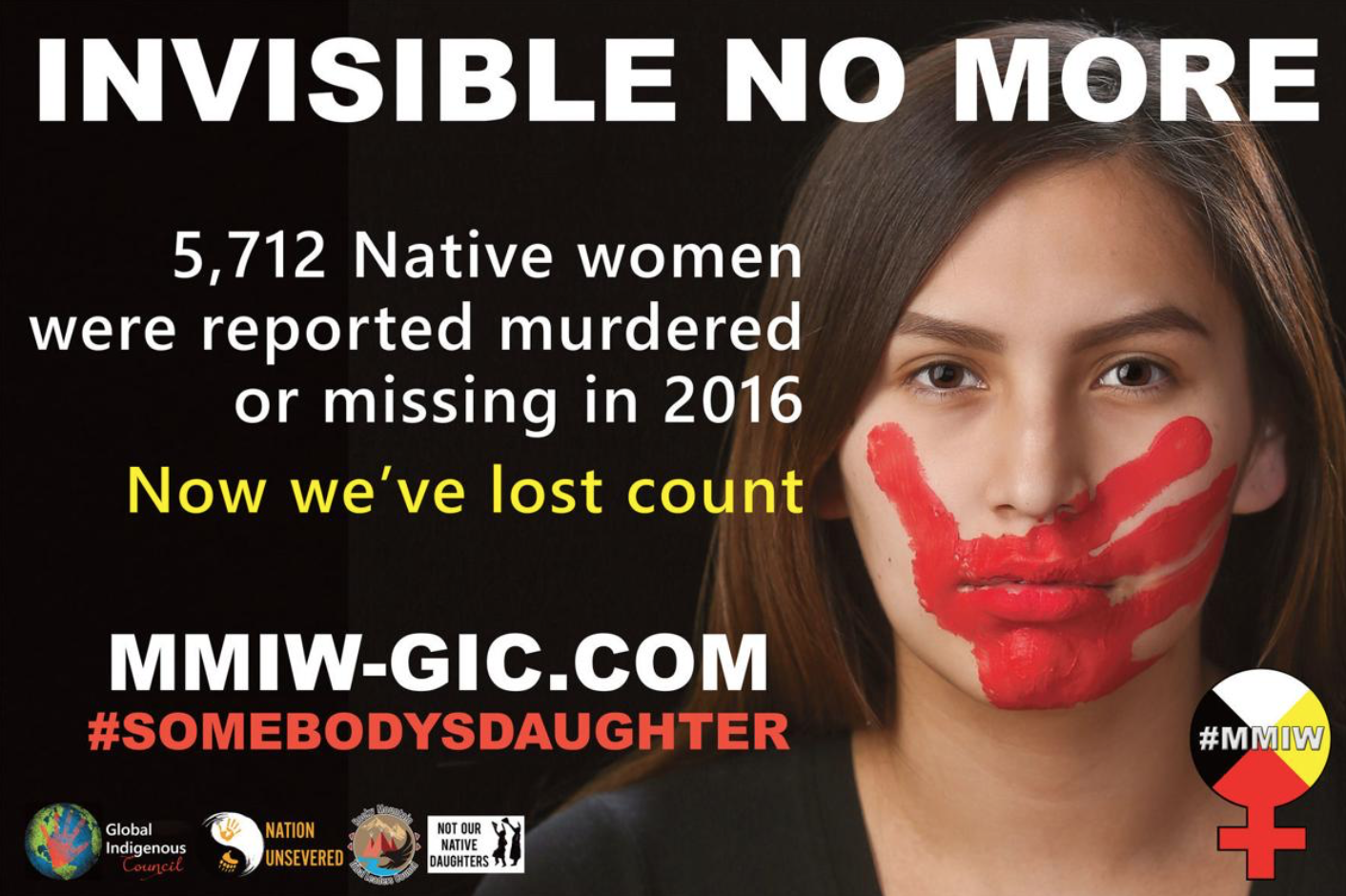

Tinoco, who is part indigenous, said she hopes having a standardized system for the state can also improve cooperation between the Wind River Reservation and off-reservation agencies. A state taskforce was formed in 2019 to explore solutions to the disproportionate number of missing and murdered indigenous people, but communication between Wyoming’s tribes and other law enforcement is still lacking.

It’s still early in the process, Tinoco says, and there’s a lot of work to be done before any bill lands on the governor’s desk. In the meantime, she and 11,000 others will keep doing what they can, united by a Facebook page and the quest to bring every missing person home.